Below are archived copies of previous GenePattern press releases. These press releases predate the current GenePattern blog.

RNA-seq: Comparing strand-specific RNA sequencing techniques

dUTP protocol emerges as the leader

By Alice McCarthy, Broad Communications

Published August 16, 2010

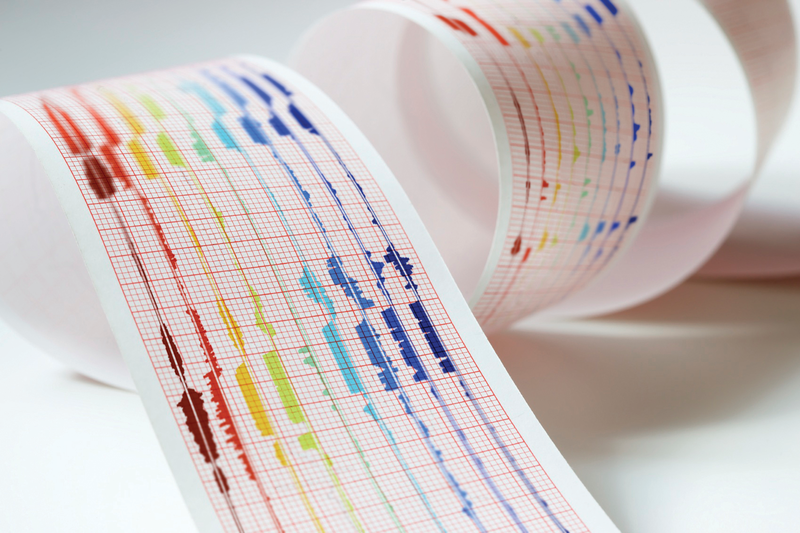

Researchers compared seven RNA-seq methods. The dUTP technique emerged as the leader.

Image courtesy of Sigrid Hart

We value having options in biomedical research. But sometimes having many choices, and without sufficient comparative information about their benefits and limitations, can unnecessarily complicate research progress. Such has been the situation over the past two years regarding the technology of complementary DNA (cDNA) "second-generation" sequencing, or "RNA-seq" as it has come to be known.

Complementary DNA is created in the laboratory starting from an RNA template using an enzyme called reverse transcriptase. The cDNA sequence is complementary to the sequence of its RNA template, hence its name. Over the past few years, researchers have developed a variety of techniques to decipher this cDNA and learn more about an organism from a cell's RNA content. In a paper published August 15 in Nature Methods, researchers at the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT directly compared seven of these methods, known as RNA-seq techniques. Using a set of criteria, a technique known as dUTP second-strand marking emerged as the leading protocol and has been adopted at the Broad for RNA-seq applications. Full details of this protocol are described in this paper and in the original 2009 dUTP paper by Parkhomchuk et al. in Nucleic Acids Research last year. The authors also provide a menu of comparative analysis criteria that can be applied for assessment of future RNA-seq protocols.

Researchers perform RNA-seq for three general reasons. "First, you want to know how many and which RNA transcripts are in a cell or in a sample," explains Joshua Levin, of the Genome Sequencing and Analysis Program (GSAP) at the Broad and co-first author of the paper. "With RNA-seq, you can actually count the relative number of transcripts made in each cell, which tells you something about its function."

Second, RNA-seq provides specific information for genome annotation. "It lets you identify the elements (DNA sequences) of the genome that are copied into RNA and assign them biological function," says Levin. In past years, genome annotation was done with expressed sequence tags (ESTs) but this relies on the older Sanger-based sequencing technology, which has rapidly been displaced by newer, second-generation techniques such as those provided by Illumina and others. Second-generation technologies have vastly increased access to the information-dense transcriptome.

Last, RNA-seq allows researchers to characterize RNA splicing - modifications of RNA after transcription, in which introns (nucleotide bases that are not expressed into proteins) are removed and exons (bases that are expressed) are joined. "There are programs that can predict that but you really want to have an actual experiment that tells you what sequences are present in spliced RNAs and those that are not," says Levin. Differences in RNA splicing can lead to alterations in the proteins translated from those RNAs thereby imparting functional consequences for cells and organisms.

Levin's group worked with various RNA-seq methods as they became available, including two developed internally at the Broad. "Though we've been working with these techniques for several years, we realized that no one had compared them to determine which would be the best to recommend," says Levin. "A lot of people are just getting started on RNA-seq so they don't know which method they should use." Researchers at the Broad often field technique-related questions from other investigators. This analysis was done largely to help the larger community sift through the options regarding RNA-seq.

In the cell, each single-stranded RNA is synthesized from one of the two strands of DNA. When RNA is copied back into cDNA for RNA-seq in the lab, the information about which of the two strands of DNA was copied into RNA can be lost unless special methods are used. The crux of this paper is to test which of seven different "strand-specific" methods is best to preserve this strand information. Strand-specific RNA-seq improves on standard RNA-seq in three ways: accurately identifying antisense transcripts, determining the transcribed strand of non-coding RNAs (e.g. lincRNAs), and demarcating the boundaries of closely situated or overlapping genes.

"Nonstrand-specific RNA sequencing has been the standard method," explains Levin. "But now strand-specific approaches provide additional valuable information and do not involve that much more work or cost."

Along with strand specificity, the team examined other criteria using their new computational pipeline. And they assessed practical measures like ease of use in the laboratory and in computational analysis. "Looking at all these factors, dUTP turned out to be the one we liked the most and it is our default RNA-seq method at the Broad right now," says Levin. But he notes that technical challenges need to be addressed to make the process high-throughput. "This technique works for making 12 libraries, for example," he says. "But if you want to automate it, for 100 or more libraries at a time, the method needs to be modified." He comments that researchers at the Broad are addressing this point now to be ready for large sequencing requests as they become more frequent.

The team's analysis is freely available on the GenePattern server. "This was done so that other researchers can evaluate their own protocols using the same criteria explained in the paper," explains Moran Yassour of the Broad Institute and the Hebrew University, and a co-first author of the paper.

Paper(s) cited:

Joshua Z Levin, Moran Yassour, et al. Comprehensive comparative analysis of strand-specific RNA sequencing methods. Nature Methods. 15 August 2010. doi:10.1038/NMETH.1491

Broad Institute researchers expand the capabilities of GenePattern software

By Nicole Davis, Communications

Published April 27, 2006

Scientists at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard recently released GenePattern 2.0, an enhanced version of the integrative software tool for analyzing gene expression data. As described in the May issue of Nature Genetics, GenePattern provides a variety of analytic and visualization functions that enable researchers to perform custom data analyses and to record them for later playback. The updated software includes several new components that permit the analysis of proteomic data and improve its ability to capture and recall the individual steps in the analytic process. GenePattern is freely available to the research community and provides multiple user interfaces, which accommodate the needs of researchers with programming experience as well as those without it.

"The strengths that GenePattern brings to gene expression analysis can now be similarly realized for proteomic data," said Michael Reich, lead author of the Nature Genetics letter, manager of cancer informatics development at the Broad Institute, and the group leader for GenePattern. "We have also added features to improve its ability to capture and reproduce analyses, which is vital to researchers both individually and as a community."

The new additions to GenePattern enable researchers to process proteomic data and include modules for data processing, analysis, and visualization. Other enhancements supplement its reproducibility features, which include automatically recording the individual steps in an analytic process so they can be repeated or shared with other researchers, and storing both the data and all versions of the methodologies used to manipulate them. These aspects of GenePattern are key facilitators for replicating in silico research findings by independent researchers.

"GenePattern meets the ever-changing needs of researchers in the age of genomic science," said Jill Mesirov, senior author of the Nature Genetics letter, chief informatics officer, and director of Computational Biology and Bioinformatics at the Broad Institute. "These new capabilities are a vivid illustration of the tool's flexibility and adaptability, as well as our commitment to the goal of reproducible research."

In the future, scientists plan to incorporate additional improvements to the GenePattern software. These include capabilities for analyzing single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) data, such as copy number estimation, loss of heterozygosity determination, and the identification of chromosomal amplifications and deletions. This information forms the core components for discovering the genomic alterations that contribute to cancer and other human diseases.

Currently, there are over 2,300 registered GenePattern users worldwide, including more than 500 institutions and 30 pharma-biotech companies. In 2005, GenePattern received the Editor's Choice award in the Bio-IT World Best Practices competition.

The updated software and a comprehensive list of new features and fixes can be found on the GenePattern website.

GenePattern is supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health.

Reich M1, Liefeld T1, Gould J1, Tamayo P1, Mesirov JP1. GenePattern 2.0 Nature Genetics; doi:10.1038/ng1785

1Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA 02142

GenePattern receives Bio-IT World Best Practices award

By Broad Institute Communications

Published July 6, 2005

The GenePattern team

Left to right: Charlotte Henson, Josh Gould, Jill Mesirov, Michael Reich, Ted Liefeld, and Pablo Tamayo.

Not pictured: Gad Getz, Jim Lerner, Stefano Monti, Ken Ross, and Aravind Subramanian

GenePattern, a gene expression analysis software package developed by researchers from the Broad Institute, was chosen for an Editor's Choice award at the 2005 Bio-IT World Best Practices celebration on June 28. The freely available application was selected for this award from 33 different submissions by a panel of computational biology experts.

"We are thrilled by this honor. Improving research practices is one of GenePattern's basic goals," said Michael Reich, manager of cancer informatics development and group leader for GenePattern. "As this tool helps accelerate genomic research, we look forward to its results - a quickened pace of scientific discovery and insight into biological processes and the causes of disease."

The GenePattern software package allows researchers to use a wide variety of methodologies to analyze gene expression data. It is also part of a larger architecture that addresses more general challenges in computational genomic research: the need to add new analysis tools quickly and easily, the need to reproduce the results of complex in silico analyses that require the coordination of different tools, and the need for a range of interfaces that make analyses accessible to non-programming researchers without limiting the full power of a tool to more experienced users.

GenePattern was recently selected by the Harvard Medical School-Partners Healthcare Center for Genetics and Genomics (HPCGG) for integration with their GIGPAD (Gateway for Integrated Genomics-Proteomics Application and Data) informatics system. "GenePattern is the best solution for integrating bioinformatics processing capabilities into GIGPAD's research and clinical process flows. We've been very pleased with GenePattern's functionality and well thought out implementation," said Samuel Aronson, director of information technology at the HPCGG. GIGPAD also received a 2005 Bio-IT World Best Practices award.

"This is a well-deserved reward for the GenePattern team," said Jill Mesirov, principal investigator and director of Computational Biology and Bioinformatics at the Broad Institute. "They made our vision for GenePattern - ease of use, interoperability, reproducibility, and flexibility - a reality."

Broad researchers recently released GenePattern 1.4, an enhanced version of the software package. For a comprehensive list of new features and fixes, and free access to the software, visit the GenePattern web site http://www.genepattern.org.

The 2005 Bio-IT World Best Practices celebration took place at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C. Submissions for the awards came from academic institutions, pharmaceutical and biotech companies.

Originally made available to the scientific community in 2004, there are currently 1,100 GenePattern users, including more than 500 institutions and 30 pharma-biotech companies across 35 countries worldwide.

In addition to Mesirov and Reich, members of the GenePattern development team include: Gad Getz, Josh Gould, Charlotte Henson, Jim Lerner, Ted Liefeld, Stefano Monti, Ken Ross, Pablo Tamayo, and Aravind Subramanian.

The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health.

Broad Institute researchers release GenePattern 1.4

By Broad Institute Communications

Published June 17, 2005

![]()

Recently, researchers at the Broad Institute released GenePattern 1.4, an enhanced version of the microarray analysis package that is freely available to the scientific community.

GenePattern addresses several hurdles facing biomedical research, particularly the need for interoperable tools and reproducible in silico research in bioinformatics. It provides an accessible yet sophisticated analytical tool, with the ability to support novel approaches to analysis, while unifying investigative methods across disciplines.

Major new features of GenePattern 1.4 include:

- Functionality for reproducible research - Researchers can capture and package entire methodologies and export the information to colleagues for easy reproduction of analyses. This also provides researchers with the option of publishing in silico studies as a supplement to publications.

- File navigation aids - Users can right-click on any file to view analysis options that can be run on a selected file.

- Industry standard compatibility - Researchers can work in MAGE-ML format, as well as download data from the Gene Expression Omnibus database.

The updated software and a comprehensive list of new features and fixes can be found on the GenePattern web site http://www.genepattern.org.

Currently, there are 1,100 GenePattern users, including more than 500 institutions and 30 pharma-biotech companies across 35 countries worldwide.

Broad Institute researchers release enhanced GenePattern software

By Broad Institute Communications

Published September 23, 2004

Recently, researchers at Broad Institute released GenePattern 1.2, an enhanced version of the GenePattern microarray analysis package that is freely available to the scientific community

The software offers an efficient, flexible microarray analysis tool that allows biomedical researchers across disciplines to perform custom gene expression analysis experiments, record and replay analyses, and use tools from many different software sources within a single interface. Major new features of GenePattern 1.2 include:

- Online module repository. A repository at the Broad Institute website allows users to identify, and select for automatic download, the modules they wish to import into the GenePattern system. This feature allows easy and automatic update of GenePattern as new modules are released.

- Java Programming Environment. A programming library allows Java programmers to call any GenePattern module from within a Java application. Users can also save analysis pipelines as Java applications.

- Batch analyses. A user can select a folder instead of a single file as input to a module, and the analysis will run on all of the files within that folder.

The GenePattern 1.2 software and a comprehensive list of new features and fixes can be found on the GenePattern website.

Currently, over 200 institutions, including more than 30 pharma-biotech companies, across 35 countries worldwide, are using the software package.

GenePattern was developed with funding from the National Cancer Institute through a grant from the Biomedical Information Science and Technology Initiative of the National Institutes of Health. This grant was awarded to principal investigator Jill Mesirov, chief informatics officer and director of the Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Organization at Broad.

The Broad Institute (rhymes with "code") is known officially as The Eli and Edythe L. Broad Institute. It is a research collaboration of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Harvard University and its hospitals and the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research. The Broad mission is to create comprehensive tools for genomic medicine, make them freely available to scientists worldwide and pioneer their application to understand and treat disease.